It’s early morning and the house is still asleep. Outside the sky is clear and I see some mountains warming up in the sunlight. Down here in the valley it’s still freezing. A late spring frost that lives little chance to the frail flowers of the fruit trees. Surely very few plums or pears this year. The apples might be spared for the apple trees are not in full bloom yet.

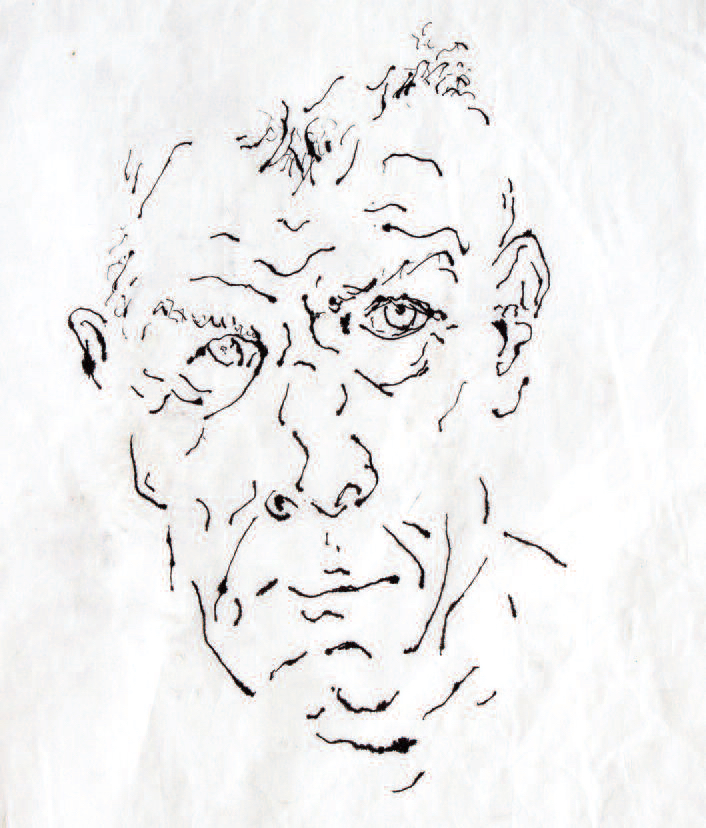

Drawing my father in his coffin ; is there words I can put next to the memory of this experience ? Drawing is a speechless activity. Or rather the place where it takes us is beyond any verbal language. As I was drawing time was turned inside out, turned on the side of the dead.

My father drew both his parents after they died. Of his father Stanley he drew a simple portrait, done with a light pencil on a standard letter paper. I remember it as being a profile, but strangely when I try to make it come back to my memory, I start seeing the other side of the face. I might search for it to check but for now I stay with this image belonging to my childhood, at the time when this drawing was hanging on a wall of our house.

Since then, I’ve seen several drawings of fathers, mothers, loved ones, dead and mourned by the one drawing them. An despite the differences between this portraits, I feel they all have something in common. Something strong enough to make one sense a kind of likeness. They seem to be all part of the same family, an old family belonging to another time. Unlimited.

I follow the line of his nose. It seems smaller than it did. The two black holes of his nostrils attract my gaze and I enter the depth of these tunnels. I press stronger on the pencil. The mouth is loose. Falling down as to say. One side more than the other. Again a thin dark line marks the entrance of a cavity that sucks me into its boundless night. The lips are dry tender, even in their immobility. His famous chin divided by a line surrounded by recently shaved hairs of his non existent beard.

I know his skin is cold but when drawing him it doesn’t feel so. Its temperature is the one it always was.

Nothing like drawing recalls and keeps the faces of the ones who have left us. For in its appearance it expresses what relates the dead to the ones he is living. Something there is no words for. In fact neither any image of. Because it’s all inside us;

His eyes. Drawing his eyes closed. Of course closed for ever, but in fact that doesn’t make such a difference. The fact is I can see those eyes that can’t see. The way the eye broth rest, curled up, against the skin under the eye, before the ocular cavity. What is more fragile, and therefor lovable, than eyes closed ? My hand holding the pencil gently turns around the eyeball. Under and over the wrinkled skin. I’m not looking at what’s happening on the paper yet. God damned the drawing ! Look at this head and see its life now that it came to a conclusion. See the way the bones appear more prominently, as if they had won a battle. And it’s true that now the tissues of the face no longer resist but follow the lines and shapes dictated by the skull. But in this abandon, something of the person previously living, is still there.

Between the day my father died and the day we buried him, several of u, family or close friend, visited the chapel where his body was resting. Each of us has different ways of saying good bye. Some touch, stroke, or kiss. Some don’t. Many say he’s beautiful. Four of us draw him. We know he would have drawn. Exactly like he did with me in this same place, three and a half years ago, when our Beverly was lying in a similar coffin.

In face of mystery one can’t always do much. Some pray, some sing, some scream and some don’t. Drawing is a way of acting with what’s happening. Might it be as terrible and natural as somebody dead, it helps to see the beauty that despite all, or with all, exists because human.

The day has passed. It’s dark now outside. It’s starting to freeze again. The sky is clear with stars.

2017

Dessiner mon père

Traduction Nancy Huston

Il est tôt le matin et la maisonnée dort encore. Dehors le ciel est dégagé et je vois des montagnes qui se réchauffent aux rayons du soleil. Ici dans la vallée il gèle encore, une tardive gelée printanière qui donne peu de chances aux fragiles fleurs des arbres fruitiers. Sûrement très peu de prunes ou de poires cette année, les pommes seront peut-être épargnées car les pommiers ne sont pas encore pleinement en fleur.

Dessiner mon père dans son cercueil : suis-je capable de juxtaposer des mots au souvenir de cette expérience ? Le dessin est une activité muette. Ou plutôt, le lieu auquel il nous conduit se situe au-delà de tout langage verbal. Là où le temps s’inverse, comme s’il se trouvait du côté des morts.

Mon père avait dessiné ses deux parents après leur mort. De son père Stanley il a fait un portrait simple, au graphite léger, sur une feuille de papier à lettres. C’est un profil de trois-quarts, en fermant les yeux je peux le visualiser assez précisément. Une image appartenant à mon enfance, du temps où elle était accrochée au mur de notre cuisine.

Depuis lors, j’ai vu plusieurs dessins de morts – pères, mères ou proches, pleurés par la personne qui les dessinait. Et même si ces “derniers portraits” sont très différents les uns des autres, il me semble qu’ils ont aussi quelque chose en commun. On dirait qu’ils font partie d’un même lieu et d’une même vieille famille.

Le temps où ils existent est sans borne.

Je suis la ligne de son nez. Il me paraît plus petit qu’auparavant. Les trous noirs de ses narines attirent mon regard et je plonge au fond de ces tunnels. J’appuie plus fortement sur le crayon. La bouche est relâchée, comme tombée. Un côté est plus bas que l’autre. Là encore, un mince trait sombre marque l’entrée d’une cavité qui m’aspire dans sa nuit sans fin. Les lèvres sont sèches et tendres, même dans leur immobilité. Le célèbre menton fendu rejoint la pente du cou épais.Je sais que sa peau est froide, mais en le dessinant je ne le sens pas. Elle a la température qu’elle a toujours eue.

Rien ne rappelle ni ne préserve le visage de ceux qui nous ont quittés comme peut le faire un dessin, dont l’apparence exprime ce qui relie les morts à ceux qui restent. Chose qu’aucun mot ne peut exprimer. Chose invisible qui n’existe que dans notre for intérieur.

Ses yeux. Dessiner ses yeux fermés. Fermés à jamais, bien sûr, mais pour le moment cela n’a pas tant d’importance. Le fait est que moi je vois ces yeux qui ne voient pas. La manière dont les cils reposent, recourbés, sur la peau au-dessous de l’œil, près de la cavité oculaire. Quoi de plus fragile, donc de plus aimable, que des yeux fermés ? Ma main qui tient le crayon tourne doucement autour du globe oculaire, sous et par-dessus la peau ridée. Je ne regarde pas encore ce qui se passe sur le papier. Au diable le dessin ! Regarde cette tête et vois sa vie, maintenant qu’elle est arrivée à sa conclusion. Vois comme les os ont l’air de saillir, comme s’ils avaient emporté une bataille. La chair du visage ne résiste plus, elle suit les lignes et les formes dictées par le crâne. Mais, même en cet abandon, subsiste quelque chose de la personne naguère vivante.

Entre le jour où mon père est mort et le jour où nous l’avons enterré, plusieurs d’entre nous, parents ou amis proches, avons visité la chapelle ou reposait son corps. Chacun lui a dit adieu à sa manière. Certains ont touché, caressé, embrassé, d’autres non. Plusieurs ont dit qu’il était beau. Quatre d’entre nous l’avons dessiné. Lui, on le sait, aurait dessiné. Exactement comme il avait fait avec moi en ces mêmes lieux il y a trois ans et demi, quand notre Beverly gisait dans un cercueil semblable.

Face au mystère, on ne peut pas toujours faire grand-chose. Certains pourraient prier, chanter ou hurler. D’autres, pour avoir une prise sur ce qui se passe, essayent de faire un dessin. Serait-il aussi terrible et naturel qu’un corps mort, il aide à voir ce qui rend ce corps beau malgré tout, ou grâce à tout, car humain.

La journée prend fin. Dehors, il fait nuit et il gèle à nouveau. Le ciel est dégagé et rempli d’étoiles.

----------------------------------

Accueil. Peintures, gravures, sculptures, écrits, bibliothèque et autres.

Homepage. Paintings, Etchings, Sculptures, Writings, Library and more.